Art & Fear

Putting yourself out there is scary. When I was first presented with this opportunity to blog, it was exciting. I have presented at conferences multiple times with plenty to share and thought, “Sure! This will be something new and fun.” Now that I sit down to write, it is downright terrifying.

But this is a good thing, right? I was reminded of the quote by Seth Godin, “If it scares you, it might be a good thing to try.” But what is so good about doing something scary? Well, if it is scary it might be a new experience (it is) and it might open you up to new perspectives (hoping so). New perspectives and new experiences help us to grow, to develop things about ourselves that weren’t there before.

Seth Godin

Writing this first post is a lot like what it feels like to make art after a long dry spell. You have to get over that hump of creative block. Your stomach might clench up in a tight knot and all those nagging voices of doubt start to bubble up in your head. You try to ignore them and dive in, frustrated at first as you shake off the cobwebs, but then you get over yourself, your doubts, and find your flow, enjoying the process for what it is - a release, a way to tap into something that fulfills you, and ultimately a way to find meaning and purpose in the creation of something that wasn’t there before.

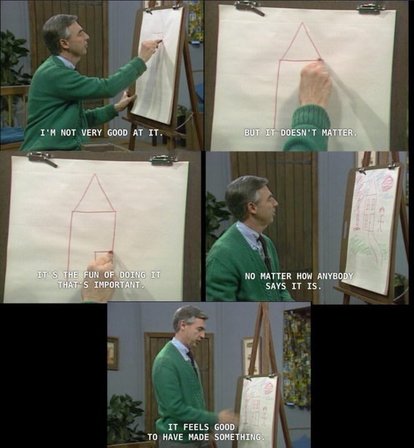

You owe it to yourself, and your students, to push yourself to try new things and to keep creating even when it is scary or feels uncomfortable. We need to give ourselves permission to try new things and to participate in small creative acts. Even small acts of creativity can snowball into greater creative acts that ultimately make it easier to think outside the box. If you are feeling stuck, look for the little ways that you can practice creative thinking. Try a new recipe, drive a different route to work, model experimenting with new media in front of your students. Feel the way your students feel when you present them with a new artistic challenge. Be ready to teach them to overcome their fears.

Fred Rogers pushing himself to create (from Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood: Episode 1481

What are some of the ways that you push yourself to be creative?

How do you teach your students to overcome their fears?

I’d love to hear about it in the comments below...

If you want to read more about the way art gets made, the reasons it often doesn’t get made, and about the difficulties that cause so many artists to give up along the way, check out the book Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking by David Bayles & Ted Orland. I love this book and recommend it to my graduating seniors.

A reminder to myself to create

something a little each day.

How do you teach your students to overcome their fears?

I’d love to hear about it in the comments below...

If you want to read more about the way art gets made, the reasons it often doesn’t get made, and about the difficulties that cause so many artists to give up along the way, check out the book Art & Fear: Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking by David Bayles & Ted Orland. I love this book and recommend it to my graduating seniors.

A reminder to myself to create

something a little each day.

A Phase ChangeReflection is a very important part of my teaching practice and a vital way I can grow as an educator. Reflecting on my practice allows me to step back from my teaching and really analyze if what I am doing with and for my students is what is best for their development and learning. I’d like to share how a time of reflective practice made a huge impact on my students and our studio practice, but first I’d like to ask you to take some time to reflect on your personal views about:

* Your theory of teaching art * Your personal philosophies and/or * Your current teaching practices How does the way you feel about art in your daily life influence the way you teach? And how does art in your daily life gel with the way you teach? Do you create art in the same way you ask your students to create? |

Pushing Myself

I had been teaching for a few years when I started to notice a shift in my students. My students seemed to be getting lazier and lazier. No, let me correct that - they weren’t lazy. There was just a lack of enthusiasm. Was I starting to get stale? I didn’t think I had lost my edge...my own excitement...my creativity in lesson planning. It wasn’t every student, but I was noticing that I had more and more students just going through the motions. I saw it the most in my Intro students, the ones who needed art “just for the credit”. My upper level printmaking students were doing fine, going along making art and developing their craft. What was it that was so different in my Intro classes?

I had been teaching for a few years when I started to notice a shift in my students. My students seemed to be getting lazier and lazier. No, let me correct that - they weren’t lazy. There was just a lack of enthusiasm. Was I starting to get stale? I didn’t think I had lost my edge...my own excitement...my creativity in lesson planning. It wasn’t every student, but I was noticing that I had more and more students just going through the motions. I saw it the most in my Intro students, the ones who needed art “just for the credit”. My upper level printmaking students were doing fine, going along making art and developing their craft. What was it that was so different in my Intro classes?

|

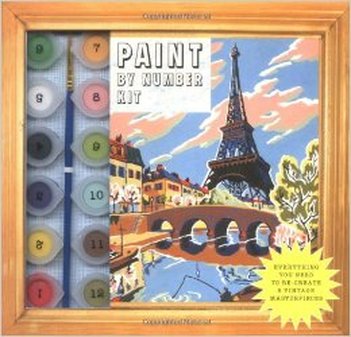

I posed this problem to my colleagues at one of our Professional Learning Community (PLC) meetings and my fellow teachers said they were seeing the same thing: a lack of motivation and a lack of creativity in the assignments. At the time, research on creativity and teaching people to be creative was scarce. Since then, many books have been written, countless TED talks have been given, and countless other teachers have realized that somewhere along the way education and a focus on standardized testing was unintentionally stripping the creativity out of kids. And I was doing the same to my art students. This had to change.

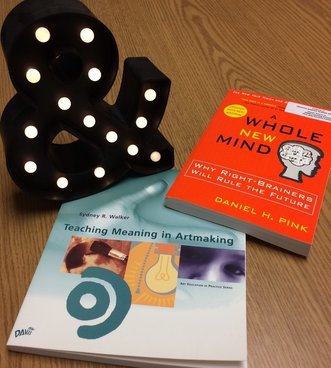

I had read and been inspired earlier by Dan Pink’s book A Whole New Mind and Sydney Walker’s Teaching Meaning in Artmaking. Neither mentioned the core of what we had been unintentionally teaching our students - how to follow directions to re-create artwork. |

|

By focusing so concretely on the elements and principles, and to a certain extent media skills, we had forgotten about making room for students to explore their own artistic connection and choices. I decided that I needed to embrace more of my own core philosophy that art is for everyone and reflected on how I could better reach my students and help them see where they connected to art. This led to my transition to focus on artistic literacy and artistic habits of mind

|

Building artistic literacy requires that students participate authentically in the arts. They need to be given the opportunity to engage with artistic processes such as imagining, investigating, constructing, and reflecting. I started to build my lessons so that they were more student-directed and less teacher-directed. I used my expertise as an artist and educator to help expose students to the way artists work, how the build their skills and when necessary, how to mine for ideas. The biggest change being that students had more opportunities for autonomy and choice so the work they created was more legitimately their own.

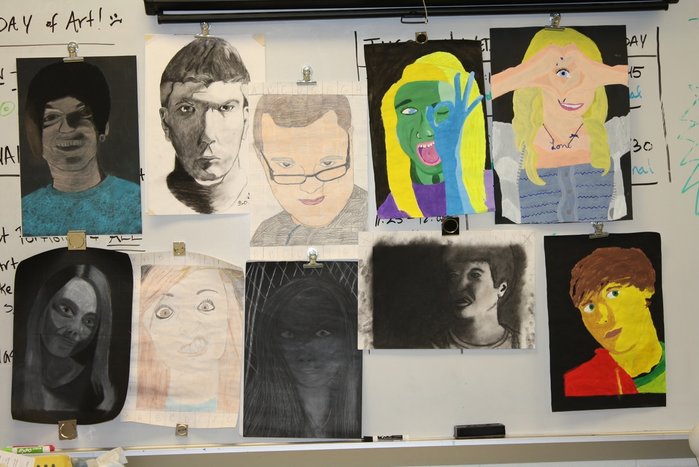

This was very difficult at first. For both my students and myself. It was actually downright scary. It scared me to let go of what I had been doing (mostly pretty successfully) to try something so dramatically different and have faith that it would be better in the long run. It was difficult to let go of the control of the learning and the resulting product to invest in the critical thinking and the overall process. It scared me to not know what would hang on those gallery walls.

I had to let them take ownership of the learning and let them come to me. The hardest part being that I had to present it in a way that piqued their interest and made them hunger for more. I had to lay it out in a way that provided purpose, allowed for autonomy, and made progress toward mastery.

And, I’m not going to lie...it was a lot of hard work. I had to take something that came very naturally to me and break it down into the parts that students could examine for themselves. I had to really think about where I got ideas, how I found ideas when none presented themselves, how did I motivate myself to keep going when I felt frustrated or when things weren’t looking the way I wanted them to? How could I encourage my students to take the lead and drive their own learning?

This was very difficult at first. For both my students and myself. It was actually downright scary. It scared me to let go of what I had been doing (mostly pretty successfully) to try something so dramatically different and have faith that it would be better in the long run. It was difficult to let go of the control of the learning and the resulting product to invest in the critical thinking and the overall process. It scared me to not know what would hang on those gallery walls.

I had to let them take ownership of the learning and let them come to me. The hardest part being that I had to present it in a way that piqued their interest and made them hunger for more. I had to lay it out in a way that provided purpose, allowed for autonomy, and made progress toward mastery.

And, I’m not going to lie...it was a lot of hard work. I had to take something that came very naturally to me and break it down into the parts that students could examine for themselves. I had to really think about where I got ideas, how I found ideas when none presented themselves, how did I motivate myself to keep going when I felt frustrated or when things weren’t looking the way I wanted them to? How could I encourage my students to take the lead and drive their own learning?

Little did I know then, that finding the answers to these questions and solutions to these obstacles would lead my students to produce their own, inspired artwork. I saw that fire of curiosity rekindled and students started to become enthusiastic learners again. I could feel I was on the right track.

How do you inspire your students to take risks in their artmaking?

Do you give them room to explore ideas and make mistakes?

How do you encourage them to develop their own line of inquiry?

How do you inspire your students to take risks in their artmaking?

Do you give them room to explore ideas and make mistakes?

How do you encourage them to develop their own line of inquiry?

A Path Towards Change

|

Once I had decided I needed to update how I was teaching to meet my students where they were coming from, it was a fun challenge to renovate my lessons. Although at times it seemed overwhelming, I reminded myself “There is only one way to eat an elephant, one bite at a time.” So I dove in to revising how I approached my first unit.

I started by taking some inspiration from one of the amazing speakers I had heard at the latest NAEA National Convention, Olivia M. Gude. Some of you may already know her and be inspired by her articles or her lectures. Hearing what Olivia had to say completely rocked my world. She has a particular knack for getting you to think about the choices you make and the impact they will have on your students. One point in particular that stuck with me was when she asked her audience to think about the amount of time spent on a two-point perspective drawing in comparison to the entire time you spend with your students in the art class. For me, I realized it was almost an entire fourth of a semester. Is that what I prioritized from my time with my students? If I really thought about what I wanted my students to remember about art after graduation, or in 20 years, was being able to to draw precise orthogonals without context or substance what I wanted them to hold on to? For me, the answer was no. |

Olivia M. Gude

Olivia M. Gude

Olivia M. Gude

(For more thoughts from Olivia M. Gude, I invite you to check out her articles written for Art Education or her Digication e-portfolio).

Working with a partner art teacher, I sat down to re-evaluate what I valued about art, and what we wanted our students to really appreciate and cultivate in their own learning. That was when we hit it...it was about what they valued in the learning. How could we start where they were, and bring what they were interested in learning to the forefront? How could we illuminate the connections between their personal interests and bigger concepts in art? Where could they find meaning?

|

We started by asking our high school students to think about how art and visual images communicate. Where do they see visual images and what kind of messages do they communicate? We connected what they had learned in english class about literal and figurative language to how images communicate in similar ways. We looked at artworks by Frida Kahlo and Cindy Sherman, using a loose Visual Thinking Strategy discussion style.

|

We then moved them towards using images to communicate their own messages, asking the question, “How can you communicate a message without words?” Inspired by Gude and a Spiral workshop, we examined how symbols are used to quickly communicate a message and appropriated street signs to communicate new messages.

|

We scaffolded student thinking, showing them examples of how artists working in the past and today communicate without words. We examined artists like Keith Haring who developed his own system of symbols, as well as his influences from calligraphy to graffiti as well as the artists who inspired him such as Andy Warhol who used images of objects and well-known people to reflect cultural values of the time. We discussed the complex idea of semiotics, creating our own images and interpretations of words like Power or Success. Students asked their own questions about how color can affect meaning and how does size change the feel of a composition? Once we had them asking the questions, we knew we were headed in the right direction. We pushed students to think about what they were seeing in new ways, and encouraged experimentation and play. |

Students thought about questions like “How do artists communicate a sense of identity?” and “How can I communicate a sense of identity?” Students examined non-traditional portraits and how objects can represent people. We returned to Andy Warhol’s shoes and how he used shoes to represent people.

|

Then we turned it over to them. How would you represent your culture of today? How would you reflect what is going on in the world and what is important to you in it? How do you see yourself today? We encouraged students to experiment with mixed media after showing them a variety of media and techniques. We used the three tenants of motivation (autonomy, mastery, and purpose) to push their intrinsic motivation and downplayed the number grade, instead getting them to focus on making progress toward some growth in an area of personal interest such as an artistic habit or skill.

We saw a real departure from the recreated artworks of the past, and a massive difference in student attitudes and interest. By asking provocative questions and exposing students to the work of professional artists, we were inspiring creative practices that had led to some truly meaningful work from our students. It also reignited our passion in the classroom, giving us a jolt of energy we hadn’t quite realized we were needing as art educators. |

What kind of provocative questions do you ask of your students?

How do you expose your students to artists working today?

How do you keep yourself asking questions and where do you turn for your dose of artistic inspiration?

How do you expose your students to artists working today?

How do you keep yourself asking questions and where do you turn for your dose of artistic inspiration?

Moving to Inquiry

|

Asking students provocative questions had led us down a path of inquiry that truly worked well for our students. So much so, that when it came time to re-write our curriculum, we pushed forward with adopting the newly revised National Core Arts Standards and an inquiry-based format for our model lessons.

|

Alice in Wonderland “Curiouser and curiouser.” Going down the rabbit hole.

What does it mean to teach through inquiry?

We would begin by developing unit themes and big ideas driven by essential questions to frame the unit investigation. These had to be broad enough that students could enter into the theme from multiple perspectives and explore multiple variations of their own choosing. So for example, one of our elementary units is Story with some of our questions being, “How do pictures tell stories?” “How do artists show a feeling or mood in a visual image?” “How do we use art to tell stories about people?” where as one of our advanced studio classes has a unit called State of Mind with the essential questions: “How can we see emotions?” “How do we make something internal, external?” “How do we show thoughts, ideas, or feelings without depicting recognizable objects?” “How can we depict a state of mind through art?”

We pushed ourselves to go beyond a media driven curriculum. Especially because more and more artists today are making art that defy traditional art categories. Artists make art with the media that will best execute their idea or meaning, so how do we teach our students about the expressive qualities that lie within each media choice? We promote play and experimentation, collaboration and creative explorations. We encourage students to think about ideas in multiple ways and to try them out in multiple media. We want them to gain experience and familiarity with multiple ways of expressing and representing concepts.

Inner Child by Dave B on Flickr

We avoided lessons that mimicked or copied one artist’s style or way of working. Instead, we tried to provide a variety of artists that explored a theme or similar idea in multiple ways to encourage students to explore how they would approach a theme or concept. What unique perspective do they bring to the table? We wanted students from elementary to high school to know that we valued their voice and that as their teacher, we would help them learn how to be heard. We would give them choices (sometimes limited) in their media use or in the subject matter. The balance was knowing how much or how little choice they were developmentally ready for in connection with our learning objectives. We purposefully try to expose students to a combination of artists, both traditional and contemporary, and with a variety of perspectives from diverse cultures and world views.

Multiple ways from point A to point B

We are transitioning to a focus on process over product. This is sometimes the most difficult to do because it is hard to let go of the pressure to have many “wall worthy” works of art to display in the hall or in a gallery. We feel an immense pressure to put work on display that will make adults ‘ooh’ and ‘ahh’ at the cuteness or the skill. However, as an audience we tend to judge student artists on the level of an adult or professional. Is that truly fair to children and adolescents who are just starting out? How can we as teachers shine a light on the stages of development that go into becoming an artist? What can we add to the display of artwork that illuminates the thinking behind the hard work? How can this practice encourage ownership of student learning? How might this promote a healthier growth mindset in our young artists and future artizens?

3rd Grade students working on their artwork

We decided we needed to think and talk more about art. We needed to help students learn about where to get ideas and how to nurture idea seeds to get them to grow. How do we brainstorm? How can we collaborate and offer feedback to strengthen ideas? What kind of suggestive examples, compelling role models, and diverse methods can we provide that will help students engage in meaningful art making? We are teaching students about the practice of keeping a sketchbook from the earliest grades and promoting its use to track our process from idea to fully executed work and to include the documentation of revisions. How can we use sketchbooks to talk about our ideas and the development of our work with peers and mentors?

Middle school artist hard at work

Our lessons focused on an inquiry process that roughly followed this outline:

- Engage - Hook students with juicy questions, examples of artwork, or conversations about art. Get their wheels turning in conjunction with the theme.

- Explore - We asked “Can acts of engagement and exploration be works of art in themselves?” “How do artists push beyond what they already know and readily see?” “When do exploration and experimentation become art?” This is where we encourage students to experiment with media or explore different interpretations of an idea or concept. We expose students to artists and artworks that work within a connected theme.

- Explain - This is where we may revisit individual student questions or learning needs, giving more explicit instruction. Researchers Housen & Yenawine argue that when you teach information - whether it is a concept, process, or technique – that is a genuine question of the learner, then it is more likely to be retained. Also, a summary of research on learning and cognition shows that learning for meaning leads to greater retention and use of information and ideas according to Bransford, Brown, & Cocking (2000). Students tend to be much more receptive when they saw an immediate need and use for the instruction.

- Expand - Students would then choose how they wanted to create an artwork that showed their own thought development within the unit theme. For elementary grades this may be more limited while as they advanced into high school, more leeway was given to explore broad connections. Feedback and revisions may also occur.

- Extend - Students would present their artwork to peers and others through physical displays or virtual galleries, sharing artist statements and documentation of their process along the way. Reflections may also be encouraged to be mined at a later date for further art exploration.

High school art work on display

While we started on our curriculum revisions back in 2014, and are continuing to work our way through all of our grade levels, we are beginning to see the positive impact it is having on our students. Students are more enthusiastic and take more pride in their work because it is truly the expression of their own ideas. We are seeing more authentic student art that is developmentally appropriate where we can witness the improvement of their skill and talents. And we are seeing a return of critical and creative thinking. Students are shedding the “just tell me what you want from me” look in their eye and instead we see a spark that holds future possibilities. We see students emboldened to try something new or to see “what might happen if…”. It is remarkable to see this change in our students and as teachers we are eager and excited to see them continue to grow.

How do you use inquiry in your art room? What kind of questions do you use to engage your students and provoke exploration? How has using inquiry changed the way your artists grow or your studio runs?

Tell me more...I’d love to hear about it in the comments or through Twitter. Catch me at @mridlen.